In 2025, scientists made a significant step towards understanding the pathophysiology of ME/CFS. It may not be a breakthrough, but we’re uncovering more pieces of the puzzle. It’s like fitting the corners and outer layer: we cannot yet see what the puzzle is, but we’re starting to get a glimpse of what it will show.

Let us resume our annual tradition of reviewing the most interesting ME/CFS research studies of the year and see if you agree with our optimistic assessment.

This is already the sixth year we have been making this yearly overview. Previous editions can be read here: 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020.

Genetics

DecodeME

2025 was the year of the gene. We had genetic studies on natural killer cell receptors, herpesviruses, metabolism, cytokines, and the Olduvai domain. There was one study, however, that dwarfed all others: DecodeME.

DecodeME is the largest ME/CFS study ever conducted; more than 15,000 in the United Kingdom participated by sending their DNA through the mail. Their genetic code was compared to that of 250,000 control participants. The results show that ME/CFS has a modest heritability. Genes can increase the risk of developing the illness, but they play a lesser role than in, for example, schizophrenia, Crohn’s disease, or type 1 diabetes. Further analysis by PrecisionLife suggests that ME/CFS is also highly polygenic meaning that the risk of getting the disease is spread out across many different genes, each contributing only a tiny effect.

Having one or several of these DNA variants isn’t terribly important. They increase the risk of ME/CFS ever so slightly. What matters is where they point to, as that tells us something about the biological mechanisms that cause ME/CFS. In DecodeME, most of the signals point to the brain. They include genes such as CA10, SHISA6, SOX6, LRRC7, and DCC, which are involved in neuronal development and communication in the brain. For those interested to learn more, we’ve written two articles about DecodeME: one summarizing its methods and main results, and one analyzing genes involved in ME/CFS.

Rare mutations

Before DecodeME, there was already a fascinating genetics study that had generated excitement and discussion. Mark Snyder’s team at Stanford University applied a different approach but found similar results.

DecodeME looked at common DNA variants that slightly influence how much of a protein is made. The effects are small and gradual, like turning on a volume knob. Snyder’s group, however, zoomed in on rare DNA variants that have more dramatic effects, such as making a defective protein that no longer functions properly.

The sample size was too small to capture all these rare mutations, so the Stanford researchers added a neural net trained on biological data such as protein interactions. It could map genes into networks based on their function. This allowed the analysis to indicate which networks are likely involved in ME/CFS pathology. One of the main answers was: synaptic function, or how neurons communicate with each other. This aligns pretty well with the DecodeME results.

There are, of course, limitations to these genetic studies. The sample size of the Snyder study was small (only 247 ME/CFS patients), while DecodeME replicated poorly in other genetic databases such as the UK Biobank. Nonetheless, these studies gave us an important piece of the puzzle. Theories on ME/CFS will need to incorporate these genetic clues, suggesting that the brain and neural communication are key.

Immunology

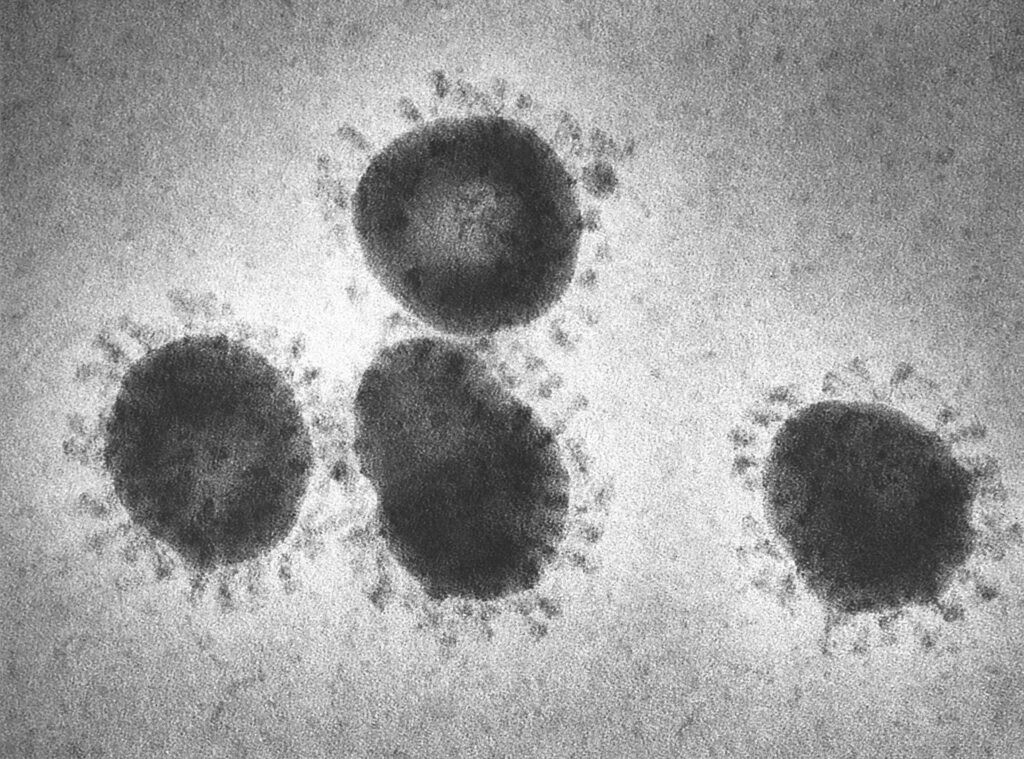

Virus hunt

DecodeME and Snyder’s study also had genetic signals pointing to the immune system. Unfortunately, most immunology studies in 2025 found null results.

Let’s start with the hunt for viruses and other pathogens. This year, the severely ill patient study from Ronald Davis’ team finally published its findings on virus sequencing. They looked at 185 human viruses in the blood but found traces of only 17. These weren’t more frequent in patients than in controls. In fact, the authors wrote that “surprisingly, more viruses were found in the healthy controls than in the ME/CFS patients.”

Iwasaki’s group also searched for pathogens in a Swedish ME/CFS cohort. They measured exposure to viruses and bacteria using antibody repertoires. For most pathogens, however, ME/CFS participants and controls did not differ in frequency of past exposure.

The most interesting study on this topic probably came from Iwijn De Vlaminck’s lab at Cornell University. They measured RNA in the blood of 93 ME/CFS patients and 75 healthy controls. RNA molecules are normally inside cells, but when cells die, some of it leaks out. By focusing on this circulating cell-free RNA in plasma, the Cornell researchers got a glimpse of what is happening in different cells and tissues. If there’s a virus hiding somewhere in the body where it’s difficult to trace, these free RNAs might reveal its presence. Unfortunately, no such clues were found. De Vlaminck and colleagues found no differences in viral RNA signatures between ME/CFS patients and controls. They caution, however, that they had little data from solid tissue.

An older multicenter study led by Ian Lipkin also found “no consistent group-specific differences” in viral particles in blood, feces, and saliva. So, if a virus or other pathogen is causing ME/CFS, it must be unusually good at hiding itself.

Antibodies

2025 also saw the most extensive study on antibodies in ME/CFS. Maureen Hanson’s group at Cornell used two advanced techniques to measure hundreds of antibodies simultaneously. The first was a 1134 autoantibody Luminex panel. This method uses microscopic beads that are dyed with specific colors so that they act as unique barcodes for different targets. The second method is called Rapid Extracellular Antigen Profiling (REAP) and was developed quite recently by Aaron Ring (who was an author on this paper). Instead of colored beads, REAP uses a library of living yeast cells where each cell displays a specific protein on its surface with a matching DNA barcode inside the cell. Using REAP, the authors could test antibodies against 6183 extracellular human proteins and 225 human viral pathogen proteins.

Even though the study had a decent sample size, no significant differences were found. Autoantibodies against G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) have been reported in ME/CFS by Carmen Scheibenbogen’s group, but were not replicated in this study. The authors conclude that “Unlike earlier reports, our analysis of 172 participants revealed no significant differences in autoantibody reactivities between ME/CFS patients and controls, including against GPCRs such as β-adrenergic receptors.”

Iwasaki’s Swedish study also screened for autoantibody reactivity in plasma and found no increase in ME/CFS patients. For almost half of the 118 antigens tested, IgM autoantibody reactivities were higher in healthy individuals than in ME/CFS patients.

The antibody theory of ME/CFS appears to be as stuck as the hunt for pathogens. Scheibenbogen’s group found increased antibodies against EBV-associated antigens, and Bhupesh Prusty’s team reported that antibodies from ME/CFS patients cause mitochondrial fragmentation inside endothelial cells. But both studies are exploratory and not yet convincing. There’s, however, a reason to remain hopeful. A treatment trial targeting antibody-producing cells shows promise. We’ll discuss this exciting Daratumumab pilot study in detail in our final section on treatments.

Heightened innate immunity

Let’s first continue with immunology: if not pathogens or autoantibodies, what else could it be? Ian Lipkin’s team at Columbia University is looking at innate immune cells of ME/CFS patients. They found that these cells have a stronger cytokine response when stimulated by a superantigen.

A superantigen can activate a large part of your immune system at once. It’s not something you want in your body as it causes toxic shock, but quite suited for triggering immune cells in the lab. Lipkin and colleagues also tested other stimuli, such as antigens that mimic a fungal infection (HKCA), a bacterial infection (LPS), or a viral infection (poly I:C). The results were as follows: no differences were found after the bacterial and viral triggers; some were seen after the fungal antigen, while the clearest changes were found for the superantigen. The authors conducted these experiments before and after an exercise test to induce post-exertional malaise (PEM), but this didn’t have much influence on the effect.

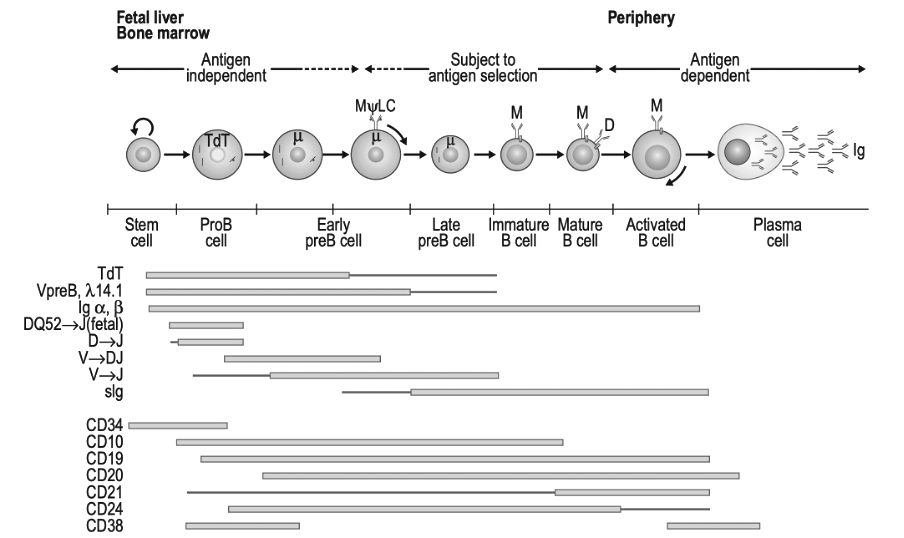

B-cell repertoires

A study by Audrey Ryback and Graeme Cowen replicated abnormalities in B-cells found by two earlier studies, namely an increase in Immunoglobulin Heavy Variable IGHV3-30.

B-cells are the immune cells that recognize pathogens and make targeted antibodies to neutralize them. These antibodies also sit on the surface of B-cells, where they act as receptors. Our immune system creates an almost endless diversity of these receptors so that it can respond to all sorts of pathogens. One way to do this is to select and rearrange the building blocks for antibodies in new B-cells, a bit like shuffling cards. IGHV3-30 is one of these building blocks. Researchers found that B-cells of ME/CFS patients used it more often in their receptors than controls.

This skewing of the B cell repertoire is normally a sign of antibody production or an immune response to a specific infection. But in these scenarios, there would also be signs of B-cells copying themselves and refining their antibodies, which Ryback & Cowen couldn’t find in ME/CFS patients. It’s therefore a bit of a mystery what it means. Some selection process must have favored this building block or made it more useful in ME/CFS patients than in controls. One caveat, however, is that the replication study only found IGHV3-30 to be more common in mild and moderate ME/CFS patients, not in those with severe ME/CFS.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC)

Two studies, one from De Vlaminck lab and one from Australia, found an increased proportion of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) in ME/CFS. These cells produce large amounts of type I interferons when they detect viral infections. Because interferons cause extreme malaise and fatigue, they have been a topic of special interest to ME/CFS research. The UK Biobank, however, found no increase in pDC in 2019, so we should probably not get too excited yet about this finding.

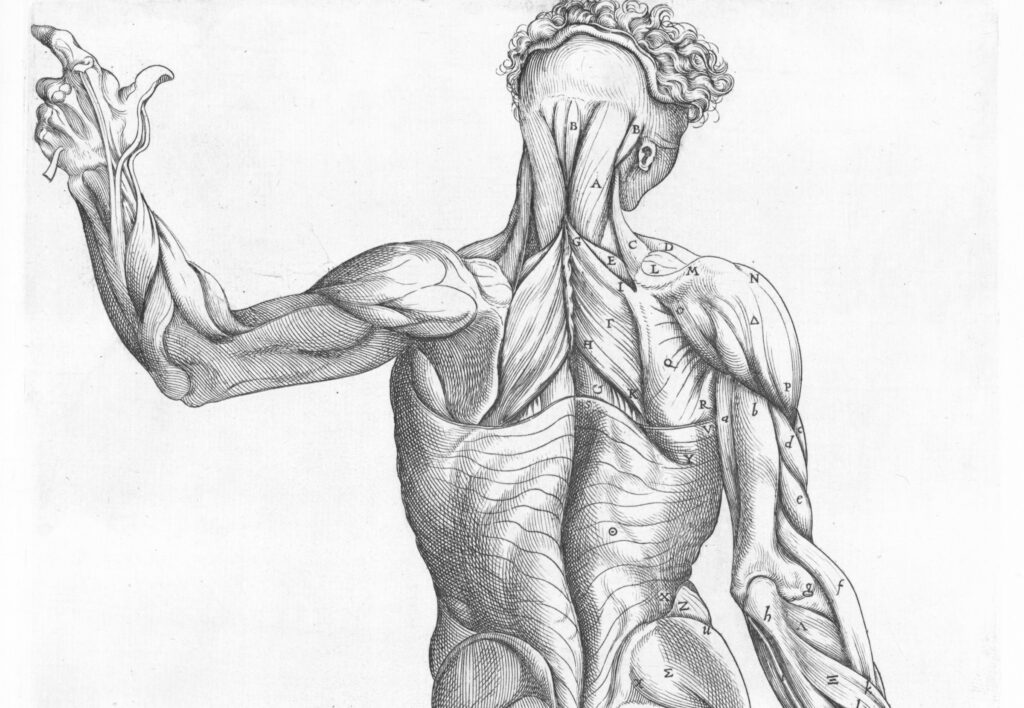

Muscles and exercise

Comparison to bed rest

The Dutch research team led by Rob Wüst is studying the muscles of ME/CFS patients in greater depth than anyone before. In a 2025 preprint, they compared ME/CFS and Long Covid patients to healthy participants who underwent 60 days of strict bed rest as part of a NASA experiment. This allowed Wüst and colleagues to study how these illnesses differ from deconditioning.

While bed rest induced severe muscle atrophy, this was not seen in ME/CFS or Long Covid. The patients’ atrophy was concentrated in type I or slow-twitch muscle fibers, which are used for endurance activities. In the bed rest participants, capillary density, the number of tiny blood vessels per area of muscle tissue, was increased, while in patients it was reduced. The authors also looked at markers of mitochondrial activity, such as succinate dehydrogenase and oxidative phosphorylation. These correlated with VO2 max in bed rest participants but not or much less so in patients. The authors concluded that “The lack of association of VO2max with mitochondrial variables suggests that their reduced exercise capacity is not solely explained by mitochondrial respiration or enzymatic activity.” The authors also expected myoglobin, a protein that binds oxygen, to be increased in patients to compensate for a reduced local oxygen supply. But it was increased in bed rest participants only, not in ME/CFS or Long Covid patients. It appears that many ME/CFS patients do not show the hallmark features of severe deconditioning.

Faulty recovery

Maureen Hanson’s group at Cornell University measured more than 6000 proteins before and after two exercise tests. Blood samples were collected at five different time points before, between and after these tests. At baseline, no protein was significantly different between patients and controls. The most interesting results were found, not immediately after the exercise tests, but after a 24-hour recovery period following the first exercise. Also intriguing: the biological pathways that were different from controls were almost all downregulated in ME/CFS patients. This was the case, for example, for ‘axon guidance’, ‘T-cell receptor signaling’, and other immune pathways. Perhaps, rather than having more muscle damage after exercise, these results suggest that ME/CFS patients’ recovery mechanism is not working properly.

Inside the muscles

This aligns with results from a Norwegian study by Karl Tronstad and colleagues. They also tested thousands of proteins in the serum of ME/CFS patients using the same aptamer method as the Hanson group. Aptamers are very small pieces of DNA or RNA that can fold and bind to a specific target, making it easier to measure lots of proteins. Because the sample size of this Norwegian study was small (54 ME/CFS patients), we’ll focus on the broad trends. While secreted proteins were increased, intracellular proteins released from skeletal muscle into the blood were reduced. This decrease is likely related to lower activity levels in ME/CFS, and it is difficult to square with the idea of increased muscle tissue damage.

There was also a study from Oxford University that applied magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to the calf muscles of 24 ME/CFS patients. These scans allowed them to look inside the muscles. They found no notable differences in creatine, acetyl-carnitine, and lipids, suggesting that patients’ muscles had no problem using fatty acids as an energy source.

Nothing in the blood

In the past years, there have been several reports on something in the blood of ME/CFS patients that disrupts the function of cells. In 2025, we got another one of these studies from Spanish researchers. They exposed healthy muscle cells to serum of ME/CFS and Long Covid patients and found a reduction in muscle contraction strength, elevated oxygen consumption, and an upregulation of genes involved in protein translation. The sample size, however, was quite small, as they used serum from only 4 ME/CFS patients and 5 Long Covid patients.

More important was the study of Audrey Ryback and colleagues. It replicated one of the earliest experiments suggesting something unusual in the blood of ME/CFS patients. In 2016, the Norwegian group of Karl Tronstad cultured muscle cells and exposed them to sera of female ME/CFS patients and healthy controls. They measured the oxygen consumption rate after adding the stressor oligomycin, an antibiotic that inhibits the creation of ATP. The study had only 12 ME/CFS patients, but the difference found was large. Cells exposed to patient sera had much higher oxygen consumption.

Ryback and colleagues redid this experiment in 67 ME/CFS patients and 53 controls but found no effect. This was a proper replication as we rarely see them in the ME/CFS field. The authors used blinding and randomization, pre-registered their analysis plan, and provided a good overview of potential limitations. The main limitations were that only a couple of their patients had severe ME/CFS, and that participants may not have been experiencing PEM on the day of sampling.

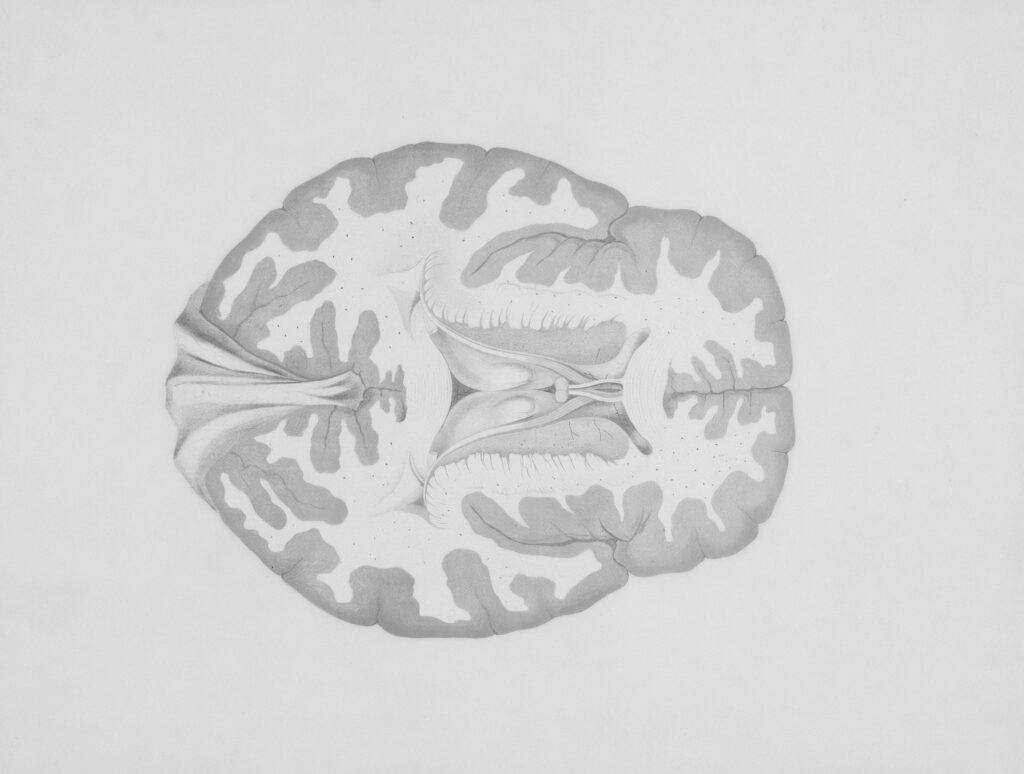

Autopsies and the stress response

There weren’t many brain scan studies in 2025, but there was a fascinating report on seven autopsies of ME/CFS patients conducted in the Netherlands. This info was shared during a presentation at the IACFS/ME conference, but the results haven’t been published yet.

Normally, we wouldn’t focus on such preliminary findings, but since ME/CFS autopsies have rarely been done and genetic data points to the brain, these findings may be of huge importance. The researchers, working at the Netherlands Brain Bank (NBB), also seem to have found something remarkable. They discovered that the deceased ME/CFS patients had almost no CRH-producing neurons. Other neurons in the hypothalamus were not affected. CRH, or ‘corticotropin-releasing hormone’, plays an important role in inducing a stress response and the production of cortisol.

Something similar was reported in type I narcolepsy. This is a rare autoimmune disease that targets the neurons that produce orexin and regulate sleep. Because of a lack of orexin, patients fall asleep uncontrollably during the day and suffer from sudden muscle weakness. In 2021, researchers conducted autopsies in five narcolepsy patients and found an 88% reduction in CRH-producing neurons. This is very similar to what has been reported for ME/CFS.

It doesn’t seem likely, however, that the immune system would attack both orexin and CRH neurons. Follow-up research suggested a different explanation: the CRH neurons probably still exist but have been epigenetically reprogrammed to no longer produce CRH. Researchers detect these neurons using antibodies that bind to CRH, so if the cells have been “silenced” epigenetically and no longer express the hormone, it would look as if they are no longer there.

We suspect that something similar occurred in the ME/CFS brains that were studied in the Netherlands Brain Bank. ME/CFS doesn’t include an autoimmune response against orexin neurons, but perhaps some other process is having the same side-effect of silencing the CRH neurons. We’re thinking about a side-effect because reports about lowered cortisol in ME/CFS have been inconsistent, and there is little evidence for a wrecked stress response. Luckily, the NBB researchers received 4-year funding from the Dutch ME/CFS program to store brains and perform autopsies. So hopefully we will know quite soon what the findings mean.

One 2025 study tied nicely with the autopsy results. The research team led by Chris Armstrong studied 135 metabolic markers, such as lipids and fatty acid ratios, using the UK Biobank. They analyzed which genes are associated with these metabolites in ME/CFS patients and controls separately. When they compared the gene associations in both groups, however, four were significantly associated with metabolic markers in the ME/CFS group only. These included SCGN, which plays an important role in the release of the stress hormone CRH, and HSD11B1, which converts cortisone into the stress hormone cortisol.

Economic burden

A couple of studies from 2025 gave us more insights into the epidemiology and impact of ME/CFS. The RECOVER study, for example, reported that adults infected with SARS-CoV-2 are approximately 5 times as likely to develop ME/CFS. Unfortunately, RECOVER assessed ME/CFS with (problematic) questionnaires rather than a clinical examination. That might explain why the incidence rate was far higher than previous estimates.

In Germany, a report by Risklayer and the ME/CFS Research Foundation estimated the economic cost of ME/CFS to be around 30 billion euros or 0.7% of GDP. It’s probably the most accurate estimate of the economic impact of ME/CFS to date. A Norwegian study found that ME/CFS also increased health problems in caregivers and that it strengthened traditional gender roles: female caregivers worked less and males more.

The MCAM study in the US found high rates of orthostatic symptoms in its cohort of 301 ME/CFS patients. In a previous article, we criticized the specificity of tilt table testing to measure orthostatic tachycardia. In this MCAM study, however, a simpler lean test was used that is less likely to overdiagnose. Approximately 10% of patients had postural orthostatic tachycardia compared to ca. 5% in controls. For orthostatic hypotension, the rates were 6% and 3%, respectively.

Leonard Jason’s team from Chicago developed a brief 10-item questionnaire to assess PEM: the DSQ-PEM-2. It has extra questions about PEM triggers, delayed onset, and prolonged recovery, and was tested in a large sample of 1534 ME/CFS patients. But patients also noted some issues. Several questions focus on everyday fatigue after exertion (rather than PEM), and many of the listed triggers, such as foods, mold, and chemicals, are not directly related to exertion.

Treatments

In 2025, we had treatment trials on rapamycin, saline infusions, Mestinon, magnetic stimulation, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. All studies, however, lacked a control group.

The one that generated the most excitement was the daratumumab pilot study. This study was done by the Norwegian oncologists Fluge and Mella, who conducted the rituximab trial several years ago. They suspect that antibodies are involved in ME/CFS pathology. They tested rituximab because it targets the CD20 protein on the surface of B-cells, immune cells that produce a lot of antibodies. Unfortunately, this hypothesis didn’t pan out as the phase III rituximab trial showed; patients on the drug fared no better than the control group.

There is, however, a group of long-lived and mature B-cells that produce lots of antibodies but do not express the CD20 protein. These are called plasma cells. They hide inside the bone marrow or gut and could have survived a short-term rituximab treatment. Instead of CD20, they express the CD38 protein on their surface. By using daratumumab, which targets CD38, Fluge and Mella hope to kill these plasma cells and stop the production of autoantibodies.

Figure 7.1 ‘Model of B-Cell Differentiation’ from the book ‘Clinical Immunology Principles and Practic, Fifth Edition’. Modified into black and white.

Their pilot trial of ten female ME/CFS patients looks promising. Four patients had no significant clinical changes, but the improvements in the other patients were quite big. The step count and physical functioning outcomes suggest some patients were close to normal levels. Also interesting: NK cells were rather low in all participants, but in those with higher levels, the treatment response was better. Fluge and Mella have started a randomized trial of daratumumab called RESETME, so we might know if this treatment works relatively soon (you can support their study here).

In the coming years, we will likely get an answer to a frequently asked question: Is ME/CFS caused by antibodies? Rituximab, which targets most B-cells, has already been trialed. The Norwegian and the Scheibenbogen group both have plans to trial drugs that target CD38 and plasma cells. There are also sham-controlled trials on immunoadsorption, where antibodies are filtered out of the blood. And importantly, the DecodeME results of the HLA-region will be published. This genetic region helps the immune system differentiate your own cells from foreign invaders. Pretty much all autoimmune diseases – multiple sclerosis, ankylosing spondylitis, type 1 diabetes, psoriasis, Hashimoto’s, etc. – show an association with HLA-variants. If all of these experiments show negative results, then the antibody theory would take a big blow and become unlikely. If any of these does show an effect, however, it would be another big piece of the puzzle. A real breakthrough.

Happy New Year

Big thanks to everyone at the Science for ME forum for their insights and discussion. These really help us to understand complex research papers.

If you think we missed a major ME/CFS study in 2025, feel free to share it in the comments below.

Wishing you all Happy Holidays and a wonderful 2026!